Introduction to Behavior Driven Development

Software development and project management is general traditionally focuses on a plan for success. This is not good enough for mission-critical and civilization scale software that also must plan for failure and for moving from failure or incompleteness to success or release regularly.

Initially, covidsim.team’s dashboard (user interface for data visualization and inputs) and related systems like our self-hosted cloud drive (collaborative editors and storage for Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Images) and supercomputer management software (custom VPS manager) were meant only for internal usage within the research team. And since I was the only one working on the system since 2015, I did not find it necessary to formalize my software development process with a development team in mind.

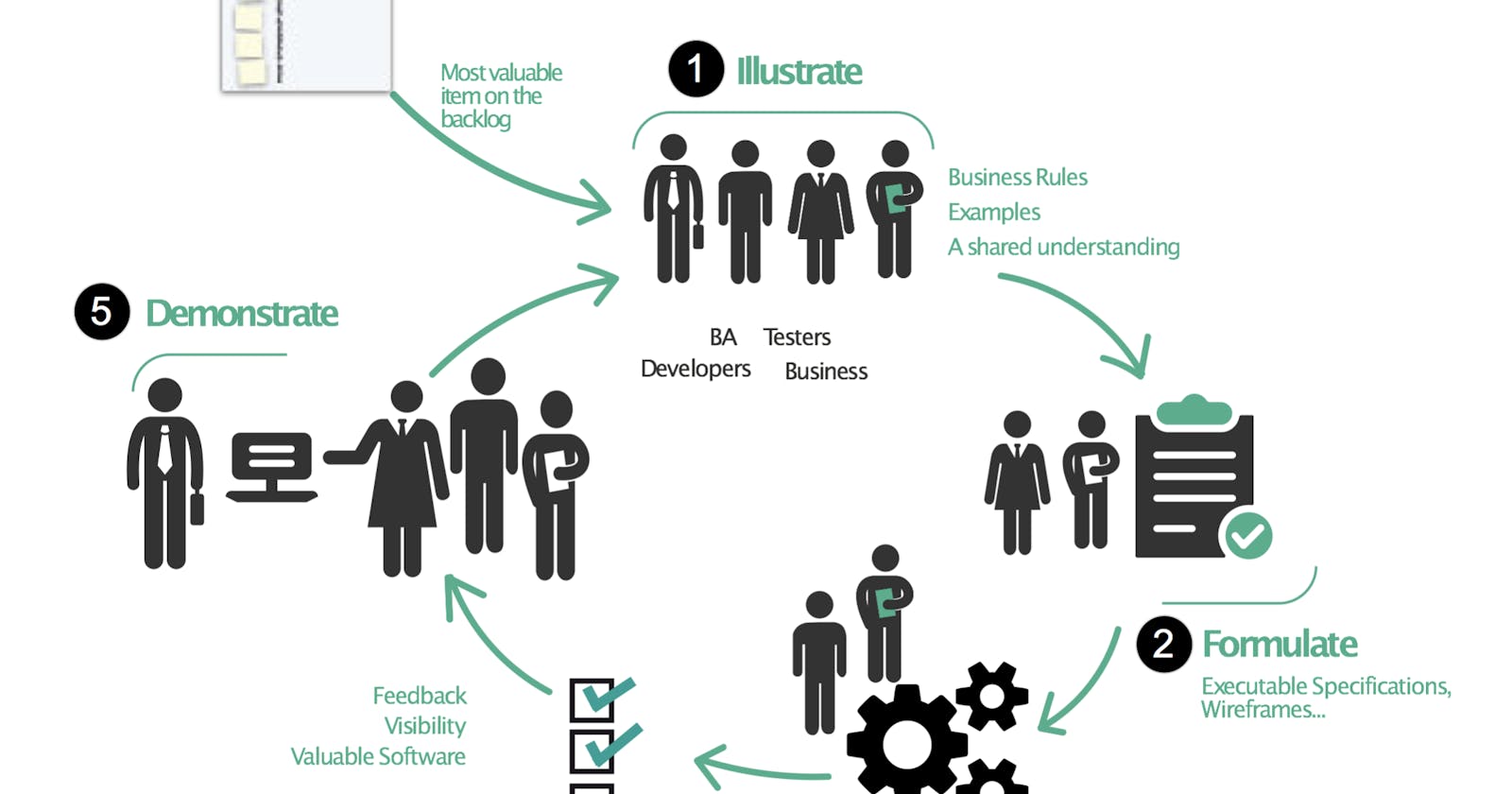

Now that covidsim.team is committed to testing the usage of some newly created forms by our public health team using this platform, we are going to need a proper development process for this national scale ambition. This BDD-based process is applicable for any quadrant in the Cynefin model.

Picture from: Harvard Business Review

These forms and visualizations of related data that we are about to roll out are quite trivial parts of the underlying system, technically speaking. However, these are the primary way for any user to interact with our COVID-specific system components currently and they effectively form a portal to the rest of my collaborative systems. Hence it is vital to us to define the behavioral specifications for each of the newly designed forms, data files or visualizations. Without a clear consensus on the new behavior, the new feature cannot - and therefore will not - be made. These specifications will be stored on cosys.work's Nepali servers only. We will require approvals and editing from a single point of contact from the customers and me or a software lead we appoint in the future. Updates to the documents should be notified via emails.

BDD Examples, Links and Resources

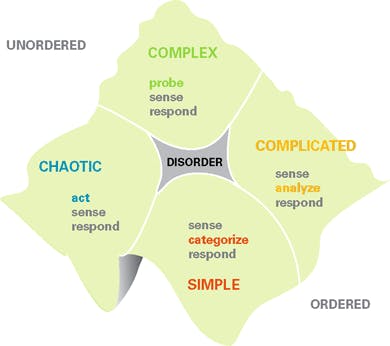

Example from: blogs.harvard.edu/markshead

A BDD feature file consists of one or more scenarios. These scenarios are just examples of how the application should behave from the standpoint of a user. For example, you might have a scenario that says:

Feature: User Login

Given I am on the login page

When I attempt to login with valid credentials

Then I am shown the application dashboard

And another scenario that says:

Given I am on the login page

When I attempt to login with invalid credentials

Then I am shown a login error message

These examples are written in English, but are still very structured. The Given portion tells the starting condition for the example, the When line tells what you actually do, and the Then tells what results are expected.

More formally speaking, the given clause is there to define the pre-conditions and context for a new feature. Similarly, the when clause is there to define the user action or a software event that may need a reaction or response from the system. Finally, the then clause is there to describe the reaction, response or output expected from the system for this scenario.

Adding feature description underneath the feature title is advisable but not usually necessary for trivial and well understood features like a normal login flow. You can also add freeform text descriptions under headers like Example, Scenario, Background, Scenario Outline and Rule followed by a colon (:) just like with Feature: above.

Another thing to note is that these Given-When-Then behavior specifications are not just documentational or prescriptive. They become a part of the source code of the software. The modules that have these specifications only perform what is specified in the Given-When-Then specs - nothing more, nothing less. These specifications and the software itself may change as frequently as the real-world requirements of the software change e.g. every second or week.

User Story -> Agreement -> Implementation

User's needs are told as user stories. Thus a user story is a story created about how a user might use the system. These are usually sent over to the development team by the customer organization or written by the project manager. A user story usually follows the format:

As a [WHO]

I want [WHAT]

So I can [WHY]

E.g.:

As an admin user

I want to be able to create and delete non-admin user accounts

So I can add new employees as users to the system whenever needed

Sometimes it is okay to just have 'As a user' as the first sentence. Since this is a common role and context, it is okay to bundle a bunch of user stories under a single 'As a user' block. After agreeing about such a story and the necessary features, a team makes a BDD spec for that user story. It will typically consist of a few Given-When-Then described features with logical connectives like 'and', 'or', 'not', 'with', 'but', 'once' or 'never'. Note that popular BDD tools like Gherkin only permit 'and', '*' and 'but' aside from 'given', 'when' and 'then'.

For example, our first user story could be about how someone from a municipality office logs in to her/his municipality’s system and what pages and data the user could expect to see and use. This story may have different scenarios e.g. whether or not the login credentials were valid, like in the earlier examples from Mark Shead.

Another user story we might need soon after launch is the story that imagines and describes how a user from EDCD/NPHL/NHRC/CCMC/MOHP could upload to the system. In this case, we may assert in the given clause that the user is already logged in. We could also create a user persona e.g. Biplav is a non-technical user at EDCD who is responsible for EDCD's side of data updates to the system every day.

So, this story could initially look like this:

Feature: CSV File Upload

Given Biplav is logged in to the dashboard

When Biplav clicks the CSV file uploader in the left sidebar

Then Biplay should be able to select, preview, review, upload or cancel the upload

These kinds of user stories may need further breakdown. This breakdown itself will also consist of more GWT sets. For example, this GWT set further explains what the system should do:

Feature: CSV File Upload

Scenario Outline: Invalid CSV File Review

Given Biplav has selected a CSV file to upload to the database using the file uploader and Biplav has not yet confirmed the upload

When The system informs him of any mistakes like "" mistake

Then Biplav should be able to edit the CSV headers and/or data before he cancels or confirms upload of the data.

Examples: Mistakes

| csv-invalid |

| invalid number of rows |

| a non-standard font or language is used |

| the file is encrypted or corrupted |

We can have many examples of inputs, outputs or options in general in the example section to clarify things.

A Given sentence can be directly followed by a Then sentence too. It is usually okay to put such statements as a rule e.g.:

Rule: Selecting an invalid CSV file should not disallow correction and eventual upload of the CSV file.

Note that we use this same structure every time because this has to be understood by software too and not just the humans.

Gherkin is a popular software interpretable GWT syntax. It is used to run behavior driven tests in the Cucumber testing framework. You can find the reference for the Gherkin syntax here.

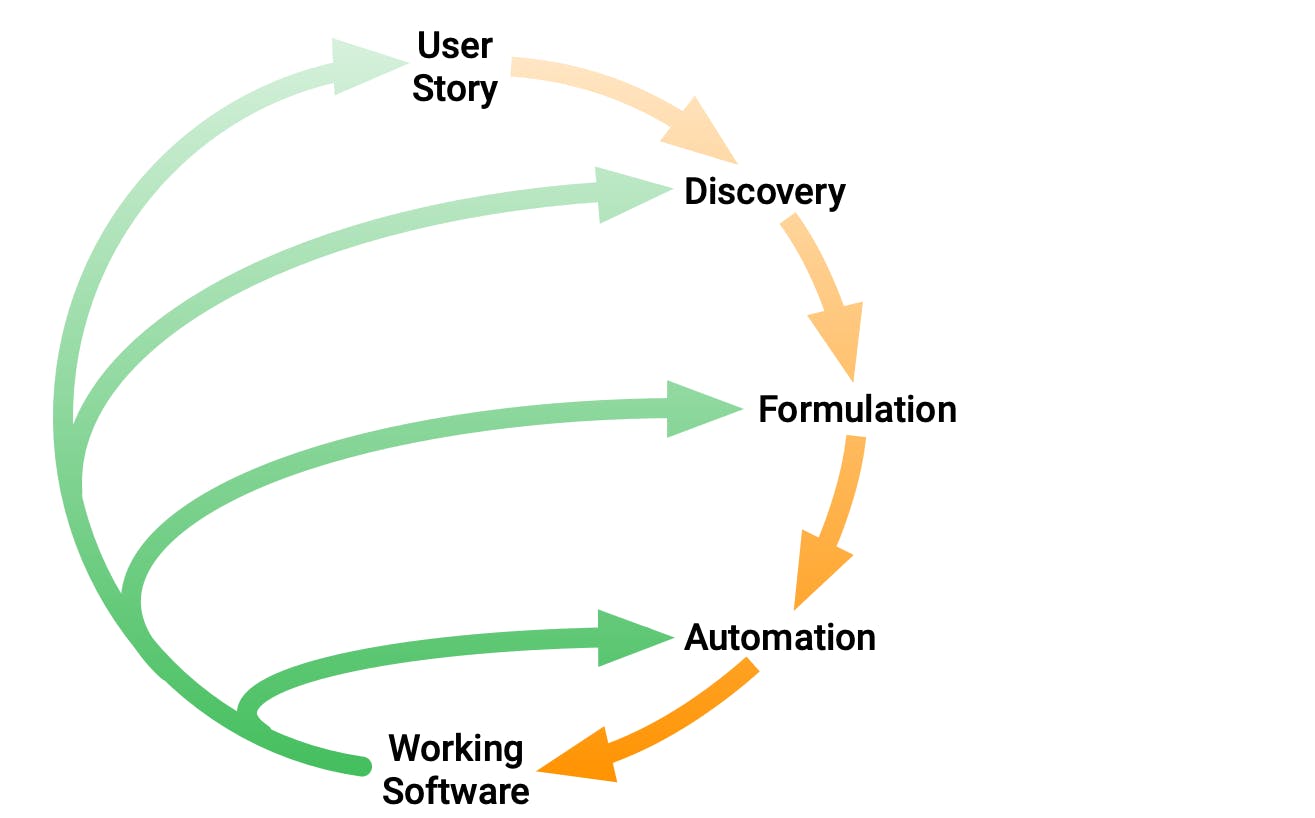

Picture from: cucumber.io

How the system could behave is a crucial part of the development process. This is the discovery phase and is typically gathered via interactive sessions and workshops with some of the potential users of the system. The discovery phase allows for surfacing and formalizing organizational rules and a shared understanding.

An even more important part of development is the finer details of how the system should behave. This is done in the formulation phase. We create specifications, mocks, wireframes and break user stories into feasible epics or tasks in this phase.

Automation phase is about how the system actually behaves. Validation and demonstration of each automated process may lead to further discoveries and formulations.