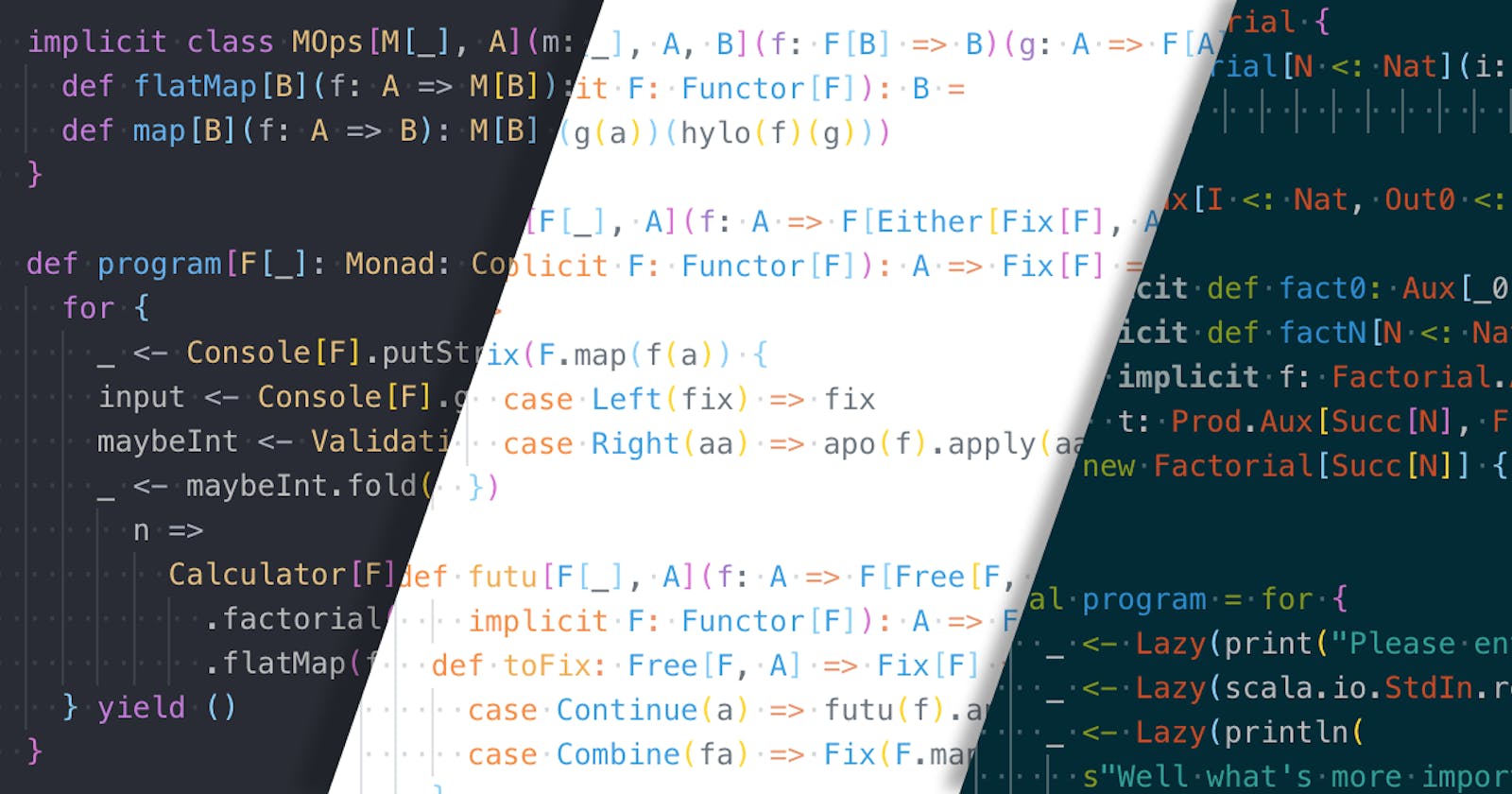

We need to invert the wasteful trend of learning something as timeless as higher maths only as a means to learn an ephemeral or ever-changing programming language or paradigm. Let's aim instead to explain and discuss foundational mathematical structures like types and categories through these programming languages as visual learning aids. This helps us become better developers in any language, including new ones for quantum computing or even natural language-based programming.

When talking about types in computer science, we could be talking about two types of types. Types from type theory are closely related to the types from from type systems used in programming languages. Both of these are fun and playing with them illuminates how any language works. It may even help you obtain A3 or perhaps even L3-tier superpowers.

Previously in the Mathematics' (An)architecture and Processes (MAP) series, we have briefly touched upon Curry-Howard-Lambek isomorphism, which is a trifecta of independent realizations about, among other things, how propositions are types i.e. claims that are true or false, formal proofs, logical calculus' constraints and formulae are types too. With Scala's types, and Java 11+'s and TypeScript's later, we will see what it actually means to say something as abstract as 'propositions are types' and why understanding these esoteric and zen sayings can make you a better programmer - in any language, with any kind of type system.

For getting started with types, we will come up with our working definition of types with increasing levels of technical depth. We will also be iteratively refining our definition and intuitions regarding what types are. As for how types look in programming, here are four simple examples:

val obligatory = "Hello World! "

// type inferred to be String based on its value

val goodbye : String = "Goodbye, cruel world..."

// type explicitly defined to be a String

val emoji: Char = '☺'

// Unicode characters are present in Char type's value space

val heteroList: List[Any] = List(obligatory + goodbye, true, 42)

// String type allows addition operation

// The composed type List[Any] allows use of any type in heteroList

This is certainly just a picture and certainly not the whole picture. However we will get closer to types through this kind of programmatic representation of types above.

This is not a pipe. This is just a representation of a pipe.

Almost every programming construct that you can use has a type. It follows that there are many types of types.

1. Common Data Types: Syntactic and Semantic bits

Let's start with the primitive ones. Types of values in data are the easiest to intuitively understand. Here at level 1, we will define type as a pre-defined value space for our data which possibly comes along with a set of allowed operations on the values in that value space.

At level 1, you may find, for instance, a type that does not have any possible operations or one that is simply an alias of another type. These are merely syntactic types. All types have this syntactic aspect in the sense that a type definition ensures the program compiler - and the programmer - that it adheres to the rules and constraints set by the programming language itself, especially regarding what is and isn't allowed to be done with a certain variable or construct.

For instance, if you find a type definition called Money in your program, it probably is a syntactic sugar representing some type of fixed or floating point numbering.

The semantic aspect of a type would be about what it means to have a certain type in the first place. For instance, type semantics could tell you what possible actions are possible on that type or what interactions are allowed with other types.

For a utility type like Money, the operations could be inherited arithmetic methods for addition or subtraction or convenience methods composed of other operations like methods for interest rate calculations.

Any and Nothing

All types in Scala are different derivations of the Any type. Informally, you may call it the mother of all types as it is the top type in Scala's type hierarchy.

Any of Scala is similar to the Object type defined by the class also named Object in Java. In TypeScript, there are two top types any and unknown. any just tells the TypeScript compiler that it should not even bother to do any type checks. So compile time type safety due to aforementioned type syntactics and semantics is effectively disabled for that variable or constant of any type. So related bugs may only be discovered if unexpected operations are performed on that value at runtime - during testing (hopefully) or in production (yikes). unknown type signifies that the actual type is yet unknown but can be narrowed down and pin-pointed based on its runtime values, usually using a language construct called type guards.

Any in Scala has general definitions of equals, hashCode and toString methods. This means that Any type in Scala allows for checking whether anything equals another and what its hashed or string representation is.

All puns intended. Always.

Type theory and category theory, from which we have type systems in programming, also have something called a bottom type. It is called so because it is at the bottom of the type hierarchy i.e. all types have the bottom type as their subtype. Scala's bottom type is called Nothing as there is nothing you can assign to a variable or construct of type Nothing. If a function throws an exception instead of returning any value, it has Nothing for a return type. We will find further uses of this in later posts, especially when we discuss covariance under parametric polymorphism.

AnyVal and AnyRef

In programming, you may be directly using or passing around a value from one memory location to another. These types of values are derived from AnyVal type in Scala, which itself is a descendant derived directly from the Any supertype.

You may also just be referring to where the value is located in your memory space instead of moving those values around. These variables have a reference type, which descends from the AnyRef supertype, which itself descends directly from the Any type.

When you look at the documentation for a type, for example Boolean, you might find methods that box or unbox a value. The scala.Boolean is a value type but you can wrap your boolean value inside a 'box' made of java.lang.Boolean, which is a reference type. You might need to do this boxing to access reference type's methods or, in this case, to ensure interoperability with Java clients of your library. Similarly, you can also 'unbox' a reference type into a value type.

Unit and Boolean

Just like Nothing allows nothing as its value, Unit allows only one and the same value, and Boolean allows only two.

Boolean type is probably the most well known and easily understood of all. It allows its value to be either true or false.

Unit type only allows one value, which is written as (). Therefore it holds no information and is very similar to, but not the same as, void used in C/C++/Java. It also should not be confused with aforementioned Nothing or with Null from the next section. We will return back to this type later when we talk about tuples and product types since Unit can be interpreted as a 0-tuple or a product of no types. We will also see how it is useful when we talk about abstract data types and algebraic data types.

Option and Null

Sometimes a reference is likely to point either to some value or none of it when the value of the instance of that type is requested for use by the program execution. In many languages, such references lead to a null pointer, which Tony Hoare, the pioneering computer scientist who introduced the null pointer concept, has famously called his billion dollar mistake.

The functional and type safe solution to this annoyance would be the the type Option or Optional (in Java, Scala, Kotlin, Swift, SML, OCaml, Rust) or Maybe (in Haskell, Agda, Idris). Depending on the implementation, this type may be monadic.

In Scala, Option is a monadic type and has two subtypes Some or None. We will discuss monads in the section on algebraic data types. For now, going by the above box or container metaphor, if you think that in your variable there maybe some value or optionally none at all then you can put it inside an Option box. To check if there are any valuables in the box, you can simply check the type of the content instead of various 'falsiness' checks or nullness checks on the value of the content itself. The type is is guaranteed to be Some if something is present or None otherwise. There also exists another similar trio called Try, Success and Failure in Scala. They essentially form a more concise syntax and are used when catching exceptions could be needed as opposed to just dealing with presence or absence of values.

We will explore examples of the usage of both of these trios when we later discuss pattern matching based on types and control flow structures like try-catch, match-case or for-yield.

The Normie Types

These are the common, necessary but boring types that will become interesting when we start composing them with other types and weaving mind-bending - and hopefully helpful - structures later.

I. Byte, Short and Int

These types have trivially defined value spaces. Available methods for each type will defer as relevant.

val u = 42 // defaults to Int type

val b: Byte = 1 // (-2^7 to 2^7-1] i.e. -128 to 127

val s: Short = 2 // (-2^15 to 2^15-1] i.e. -32,768 to 32,767

val i: Int = 3 // (-2^31 to 2^31-1] i.e. -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647

II. Long, Float and Double

These are pretty much the same as the above numerical types except they allow for bigger ranges and, in case of Float and Double, fractional values with floating point precision.

val l: Long = 1 // (-2^63 to 2^63-1]

val f: Float = 2.0 // 32-bit IEEE 754 single-precision float

// 1.40129846432481707e-45 to 3.40282346638528860e+38

val d: Double = 3.0 // 64-bit IEEE 754 double-precision float

// 4.94065645841246544e-324d to 1.79769313486231570e+308d

III. Char and String

A Char is a literal from the Unicode charset. A Char can be cast to its corresponding position in the Unicode charset as an Int, like you can in most languages.

scala> val c: Char = 'q'

c: Char = q

scala> val i: Int = c

i: Int = 113

scala> val emoji: Char = '☺'

emoji: Char = ☺

scala> emoji.toInt

res0: Int = 9786

A String is defined as a sequence of Chars. You assign a string using quotes:

val strQ = "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds - J. Robert Oppenheimer"

val listToStr = List("If I'm not back in five minutes", "just wait longer").toString

// output: List(If I'm not back in five minutes, just wait longer)

Scala String relies on java.lang.String but is also augmented by many useful utility methods from the StringOps class.

It is not necessary to learn these methods or those of any Scala type by heart. You should just get more intimate with the docs and always check the docs before writing a routine or standard looking operation on your own. You can likely also discover them using your IDE's autocomplete or inline documentations.

IV. The Big and The Rich

There are StringOps equivalents for the other the other value types called RichBoolean, RichByte, RichChar, RichDouble, RichFloat, RichInt, RichLong and RichShort. These proxies provide additional methods to the above value types. Unlike the case in Java with its primitive and boxed reference types, this pattern allows for keeping the value types lightweight while still providing a rich API and therefore fewer use cases for boxing and unboxing due to performance vs convenience trade-offs.

Besides the Rich* ones, scala.math package provides BigDecimal and BigInt classes. These are for calculations with floating-point numbers of arbitrary precision starting with a default precision approximately that of IEEE 128-bit floating point numbers.

Next on 'Types of Types'

To keep the posts from going beyond optimal lengths, we will explore each of the next 'levels' of understanding and defining types in their own posts. Here's a sneak peek.

2. Function weds Data: Domain and Co-domain Spaces

Here we will introduce functions and methods together with objects and classes. We will see how OOP augments the power of functional programming and how best to avoid the many pitfalls of OOP.

2.1 Object and Class

2.2 Functions and Methods

2.3 Parameter Types and Return Types

3. Abstract Data Types: Types with Structure and Behavior

Here we will rediscover the good old data structures mostly used in programming through a more formal, functional and scala-ble lens 🧐. Sum and product types will also pave the way for the more involved algebraic data types in the later section.

3.1 Sum and Product Types

- 3.1.1 Union or Tagged Union

- 3.1.2 Tuple and Record

3.2 Set and List

- 3.2.1 Unordered and Non-duplicated

- 3.2.2 Ordered and Random Accessible

3.3 Maps

3.4 Stack and Queue

3.5 Graph and Tree

4. Algebraic Data Types and HKTs

Here we will (re-)discover universal algebra, ring-like, group-like, lattice-like, module-like, and algebra-like algebraic structures relevant to advanced functional and reactive programming. We will also demystify higher kinded types and similarly exotic higher order concepts.

5. A Gentle Introduction to Category Theory

Here we will use the Scala concepts and Type Theory topics thus far to go for a deep dive into Bartoz Milewski's excellent course on Category Theory .

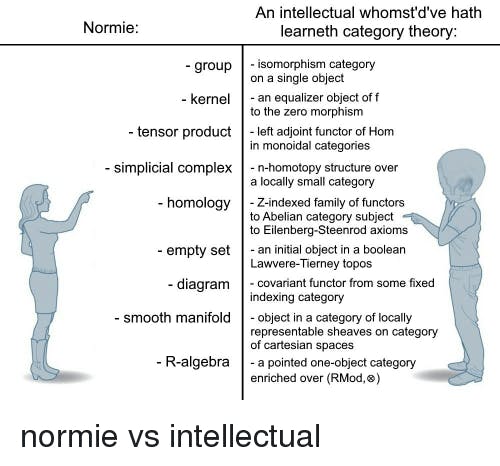

Beware that category theorists are sometimes insufferable and gave birth to memes like this one:

'A monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors, what's the problem?'

or this one below:

Further resources:

D. L. Parnas, John E. Shore, David Weiss: Abstract types defined as classes of variables, dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/942574.807133

Tony Hoare on his infamous billion dollar mistake: youtube.com/watch?v=kz7DfbOuvOM

Official Scala API Docs and resources: scala-lang.org

L.G. Meredith, Pro Scala: Monadic Design Patterns for the Web: patryshev.com/books/GregoryMeredith.pdf

Cover image stolen from: medium.com/@olxc/the-evolution-of-a-scala-p..